Safety

Flight FR4978 interception: what’s the threat response?

While the increase in security measures and passenger controls post-9/11 has helped with threats such as hijacking, the diversion of Ryanair flight FR4978 by Belarus in May shows that vulnerabilities to interference with flights remain. Alex Love explores what procedures are in place to deal with such incidents.

Image: copyright

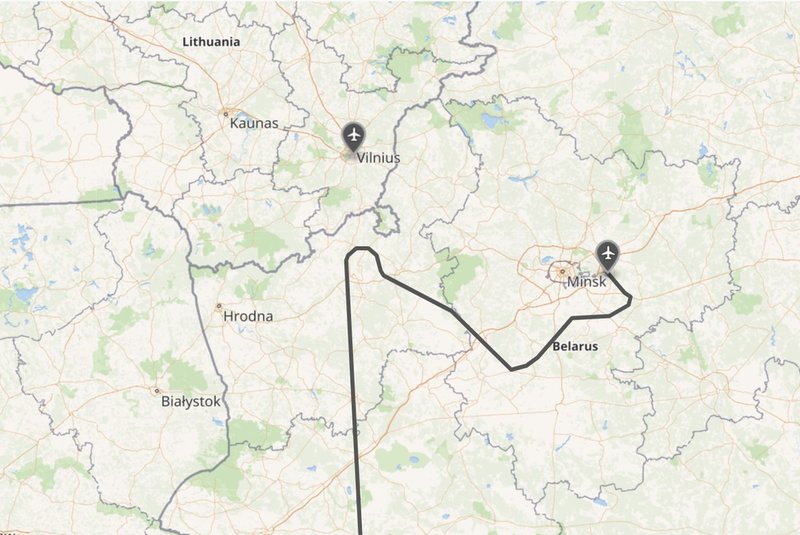

On May 23, Ryanair flight FR4978 was travelling from Athens to Vilnius Airport in Lithuania. During the flight, air traffic controllers in Belarus allegedly provided the Ryanair pilots with false information about a bomb on board to divert the plane’s flight path to land in Minsk.

Once the plane landed, local authorities arrested two of its passengers: the anti-government activist and journalist Roman Protasevich and his partner Sofia Sapega. After several hours of delays, the flight was allowed to continue to its original destination.

There were also reports that a Belarusian military jet was deployed to escort flight FR4978 to Minsk.

Authorities in Belarus have disputed all these claims, with national air force chief Igor Golub stating: “There was no interception, no forced diversion from the state border or forced landing of the Ryanair plane.”

As a consequence of the incident, the EU and UK banned Belarusian planes from their airports and suggested that airlines avoid flying over Belarus. The International Civil Aviation Organization is currently investigating the incident to determine exactly what happened.

Nevertheless, what happened on FR4978 was a reminder that despite all the increased safety procedures for air travel since 9/11, airliners remain vulnerable to outside interference while in the air.

Dealing with interference on a flight

The main priority of an aircraft crew is to ensure the safety of all the passengers on board. Any potential threats need to be taken seriously, with pilots working with air traffic control to determine the best possible course of action in the circumstances.

There are internationally recognised treaties regarding offences that take place on aircraft, notably the Tokyo Convention on Offences and Certain Other Acts Committed On Board Aircraft. This was ratified by 185 nations in 1969 and gave pilots the ability to take action in certain circumstances.

Examples of actions pilots can take include the ASSIST principle – acknowledge, separate, silence, inform, support, time. Should an aircraft get into trouble during a flight, the captain can also send a transponder code, or squawk code, over the radio to quickly and concisely let authorities know what is happening.

In the event of a hijacking, the internationally recognised code is 7500. If it is transmitted, the affected aircraft will be tracked closely by air traffic control. Military jets can also be deployed to escort the plane to the land at the nearest airport. Failure to comply could see the airliner shot down as a last resort.

There are also transponder codes for numerous other incidents such as mechanical emergencies or a communications outage.

Your training would be to take air traffic control very seriously, because their job is to look after you, not play games with you.

Training can prepare pilots for many scenarios they may one day experience in the air. However, according to ex-British Airways pilot Terry Tozer, there is no current training scenario that would have prepared a pilot for what happened on the diverted Ryanair flight.

“Your training would be to take air traffic control very seriously, because their job is to look after you, not play games with you,” says Tozer. “You wouldn't have specific training for an event like that, because I've never heard of it happening before. That's the first time I've heard air traffic control actually interfering with a flight. They just don't do that.

“The real question since this has happened is: What happens in future? The problem now is if a credible threat did come up. Let's just say there was a dispute between the country your aircraft is registered in and the country you're flying over. If they told you that there was something like [flight FR4978], would you believe them or not?”

Approximate route of Ryanair flight FR4978 being diverted to Minsk on 23 May 2021.

Threat assessment and response

Tozer says the bigger airlines have a security department, with operations specialists who assess potential threats as they occur to determine what is credible and then recommend the best course of action.

“If you're a major airline, there'll be somewhere you go through that’s dodgy,” he explains. “They have people who assess the threats, and there would be threat levels. They would have a system.”

“Major airlines have a security department. They have direct links with the security services. And BA, when I was there, would have risk levels. They had a team of people who worked on this all the time, long before September 11.

“At the end of the day, the decision always comes down to the captain. Because you only do what operations want if it's safe to do so; if the weather's all right, and all that. There are lots of variables.”

From the skipper’s point of view, an actual intercept by fighters is pretty straightforward. ICAO rules have the protocol and you don’t have much of a choice.

A commercial airliner being intercepted by a military aircraft is rare. Pilots have little option but to comply when approached by military aircraft mid-air. A pilot must ensure the safety of all passengers on board, and commercial airliners are not equipped with military-grade defences or advanced manoeuvrability.

“If the intent is hostile – or perceived to be that – there is no choice,” says Suren Ratwatte, qualified pilot and ex-CEO of Sri Lankan Airlines.

“From the skipper’s point of view, an actual intercept by fighters is pretty straightforward. ICAO rules have the protocol and you don’t have much of a choice. The safety of the passengers and aircraft is paramount, so pretty much anyone will comply.”

Impact on passenger confidence

The diversion of the Ryanair flight came at a time when the air travel industry is looking to increase flights after being largely grounded since March 2020 by Covid-19 restrictions. However, according to Gus Gardner, GlobalData associate travel and tourism analyst, the incident is not expected to affect consumer confidence in the long term.

“The interception of an aircraft by a military jet is a rare occurrence, however, it can be rather distressing for those on board. Depending on the severity of the incident, there is likely to be an impact on consumer confidence – especially if flying around the region surrounding Belarus,” says Gardner.

The fact that airlines are avoiding Belarusian airspace is a step in the right direction to restoring air travel confidence.

“The fact that airlines are avoiding Belarusian airspace is a step in the right direction to restoring air travel confidence. Governments acted swiftly, and airlines immediately implemented their advice which should have restored confidence quickly.

“However, the events have reaffirmed to passengers the importance of understanding who they are flying with and the route the aircraft will take. If passengers believed a flight might enter airspace of concern, then they are likely to think twice about booking or proceeding with their flight.

“The long-term impact of this incident is likely to be minimal. The aviation industry is incredibly resilient, passengers often forget about incidents quickly, and confidence will rise again.”

Main image: Ryanair flight FR4978 from Athens lands at Vilnius International Airport on 23 May 2021 after being intercepted and diverted to Minsk on the same day by Belarus authorities. Credit: Petras Malukas/AFP via Getty Images