Security

Finding the truth:

will airports ever use lie detectors at security?

Despite being controversial, lie detectors have been considered as an addition to airport security. With trials taking place in the US and the EU, Adele Berti takes a look at the potential of polygraphs and asks if they could be used at border control in the coming years.

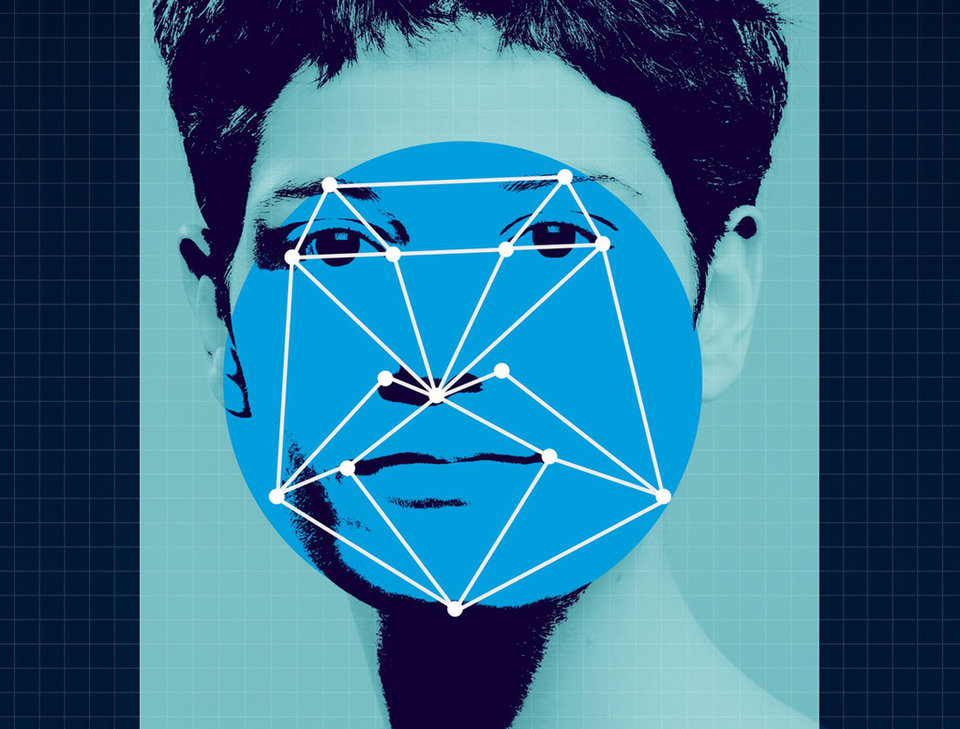

Airports have long been at the forefront of investments in new technologies. From body scanners to biometric gates, the sector has often been eager to adopt new machinery to help enhance the safety of its passengers without heavily impacting queues.

While not without controversy, the industry has often been transparent about the reasons behind its implementation of technology, which it has backed up with endless trials and research. Over time, these decisions may or may have not been approved of by the public, but they were seemingly driven by a specific need and the support of academics.

The same can hardly be said of polygraphs (popularly referred to as lie detector tests), the use of which at airports has often been marred by a lack of clarity, allegations of insufficient scientific evidence and a number of studies with unpublished results.

One such case is iBorderCTRL, an artificial intelligence-based lie detection technology that was trialled in 2018 and funded by the EU’s Horizon 2020 programme. Since its conclusion in August 2019, the results of the project are yet to be released at the time of writing.

Elsewhere in the US, the Automated Virtual Agent for Truth Assessments in Real-time (Avatar) tool uses a similar concept. Commercialised by startup Discern Science International - and based on a prototype created by the University of Arizona - Avatar also uses AI for emotion recognition with an 80%-85% accuracy rate. According to the company’s recent interview with the Financial Times, these machines could soon find a spot at airport security and potentially revolutionise it forever.

But, with widespread division on the capabilities of lie detectors among the scientific community and intense backlash from civil rights groups, will these technologies ever make it to border control?

Image:

Analysing the two technologies

According to Professor Julian Richards, co-founder of the Centre for Security and Intelligence Studies at Buckingham University, iBorderCTRL and Avatar are as similar to one another as they are different from traditional lie detectors. “The most recent systems work on a completely different basis from the traditional polygraph machine,” he explains. “They don't involve any physical wiring up or connection to the person in question. They're basically very sophisticated cameras.”

Both systems use AI to identify potentially deceiving signals in a person’s facial microexpressions. In both cases, questions are asked by a virtual border control official either prior to or upon arrival at an airport. “The screen will be looking for visual and linguistic clues from the responses that the person gives, [...]micro visual clues, facial expressions, and audio clues for tone of voice, [as well as] use of particular phraseology,” he continues.

While the organisations behind Avatar and iBordrerCTRL did not respond to a request for an interview, their websites claim feasibility studies were carried out at different airports - Romania and Arizona for Avatar and Hungary, Latvia and Greece in the case of iBorderCTRL.

While Discern Science claims Avatar’s accuracy rate is between 80% and 85%, results from the EU’s project have not yet been made public. However, an undercover investigation conducted in mid-2019 by the investigative journalism site Intercept found the technology wrongly declared four out of 16 honest answers as false.

The most recent systems work on a completely different basis from the traditional polygraph machine

The case against lie detectors

The overall lack of clarity about the programme’s findings and the European Commission’s alleged reticence to share them is resonating at an international level. In April this year, MEP Patrick Breyer called for the Commission to urgently release these results, telling EURACTIV: “The Commission has all reports on the outcome of the trials, but the Commissioner chooses to withhold information on the accuracy and bias of the dubious ‘video lie detector’ technology from Parliament. Is it because this pseudoscientific algorithm has proven to be an utter failure and useless at borders?”

The Commission replied to the allegations by saying that as a research project, iBorderCTRL “did not envisage the piloting or deployment of an actual working system”. However, this response does not explain why results have not been published.

Yet, with or without iBorderCTRL, over the past few years, the potential introduction of polygraphs to airports has been heavily criticised by civil rights groups, among which is the website iborderctrl.no. RopGonggrijp, hacker and founder of Internet service provider XS4ALL, and Vera Wilde, a PhD researcher who's been studying polygraphs for over ten years, are two of its loudest members.

“There has been a broad academic consensus for many, many decades that there is no psychophysiological basis for saying that we can detect deception,” says Wilde. “The reason for that is that there is no unique deception signal or response to detect. You can detect other things that may correlate with deception but their correlation is not one-to-one.”

Image: Nour Alnader

As she explains, issues with these machines include potential racial and gender biases and the fact that they’re often tested within mock crime studies, which makes them “highly artificial”.

“There's a lot of hype and then they don't publish their results and they quietly disappear,” adds Wilde.“There's a big graveyard of these programmes for good reason.”

She argues that this point is particularly evident in the case of iBorderCTRL, which received financial backing of €4.5m but never agreed to release any data on it - not even the study’s ethical assessment that MEP Breyer recently requested to see.

“It's fraud,” adds Gonggrijp. “There's a whole industry selling us something that doesn't exist.”

You can detect other things that may correlate with deception but their correlation is not one-to-one

Despite flaws, the technology may still have a lot to offer

However, Professor Richards believes there might soon be a place for polygraphs within an airport’s security ecosystem if they are proven to work reliably.

This is largely because before the coronavirus pandemic broke out, air passenger numbers were forecast to increase to 8.2 billion by 2037, posing several capacity challenges to the industry. “[Airports] don't want to have people having to wait for massively long periods to get through, while at the same time they want to deliver security,” he says. “So there's a massive pressure to adopt any sort of technology that will improve that process.”

Coupled with “the maturity of the technology and the extra efficiency and effectiveness it offers”, this pressure is already unlocking opportunities for lie detectors, which are starting to re-appear in some police departments. “The benefits of using it are perceived to outweigh the ethical concerns of it,” Richards adds. “And once these technologies become normalised, over time people just kind of get used to them.”

“A human interviewer can only detect a lie in about 54% of cases, which is only just over half of all cases. Sometimes they perform better than that and sometimes not.”

Image: James Bareham / The Verge

The stark contrast with Avatar’s 85% accuracy is inevitable. “If that's true and is consistent both across cases and over time, then it does mark a significant improvement on systems that we've had before and could mean that they could start to be deployed in very specific and limited ways,” Richards continues, adding: “The notion of getting 100% effectiveness is unrealistic.”

Such potential could soon be exploited at global airports, provided that the trials supporting it are constantly updated and monitored as time goes by.

As Richards explains, “these machines may become less effective as certain people get wiser to how they work but early signs show that this is a significant step forward in capability.”

A human interviewer can only detect a lie in about 54% of cases

The necessity vs ethics conundrum

More than anything, according to Richards, it’s important to think about lie detectors and airports “holistically”. “There are a number of different technologies - data processing technologies and artificial intelligence technologies - that [...] are reaching a sufficient level of maturity at the moment whereby things that used to be either unreliable or not fit for purpose before are now suddenly reaching new thresholds,” he says. “They are being seriously considered as being operationally effective and doable.”

By extension, a similar process happened with biometric e-gates and the deployment of facial recognition at airports. “There are US cities that are successfully fighting this,” says Wilde. “There have been a few US hubs that we have woken up and gone ‘well, no, this is actually not the kind of society that we want’.”

But the counterargument is that, although many are against the technology, the case for their adoption could become too compelling for airports to ignore. Richards explains: “In the same way that the biometric passports had to prove that they were working sufficiently well and weren’t disproportionately transgressing people's rights and that the data was handled appropriately, then lie detectors will be allowed to proceed too."

This is why, he says, all trials on lie detector implementation will be carefully reviewed and the machines will be subject to tough scrutiny.

“There are two competing forces out there - ethics and discomfort with this surveillance against efficiency and security, so people feeling that airports are those places where as long as you've got nothing to hide, then you've got nothing to fear,” he concludes. “I think that as the technology gets better those [sides of the argument] will win out. That's what we're seeing across the board.”

There are two competing forces out there - ethics and discomfort with this surveillance against efficiency and security