Security

Coronavirus screening at airports:

the problem with thermal detection

In January this year, several airports around the world started announcing preventive safety measures against the spread of coronavirus. However, the task has proven difficult as thermal screening isn’t always effective at detecting early signs of infection. Abi Millar reports.

In mid-January, shortly after the start of the new coronavirus (Covid-19) outbreak, a number of international airports began to announce preventative safety measures. Months later, with governments enforcing travel bans and closing their borders, demand for air travel worldwide has plummeted, airlines have cancelled/scaled back hundreds of flights, and many airports lie dormant around the world.

Since the outbreak began, some countries have introduced temperature checks for incoming travellers, to detect signs of coronavirus-related fever. As of 7 April, there have been more than a million cases of Covid-19 across more than 200 countries and over 75,000 deaths.

Initially concentrated in the Hubei province of China, where the outbreak began, the US now has the majority of recorded cases (over a quarter of a million), while the World Health Organization has called Europe the 'epicentre' of the pandemic. Travel restrictions look set to continue for the foreseeable future.

Clearly, international travel is a determining factor in the virus’ spread, and the restrictions will have gone some way towards containing it. Normally the world’s third-largest aviation market, China saw a whopping 85% reduction in airline passengers in air traffic in February. After two months of extreme travel restrictions, flight cuts and cancelled services, signs of recovery are beginning to emerge for the country.

However, some of the other measures in place are less obviously beneficial. While airport screening may help reassure the public, there is little to suggest these procedures are actually making a difference.

“Entry screening for Covid-19 involves the use of thermal scanning and/or symptom screening,” says Jeanine Pommier of the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). “Scientific evidence does not support entry screening as an efficient measure for detecting incoming travellers with infectious diseases.”

She adds that is especially the case when it comes to coronavirus, since the symptoms of the disease are so common. After all, the timing of this outbreak coincides with peak flu season in Europe and China.

Image:

The problem with thermal screening

Thermal screening at airports has long been controversial. Widely implemented during the 2003 SARS epidemic and later during the 2009 bird flu epidemic, the idea is to detect anyone with elevated body temperature and therefore a possible infectious disease.

Methods include full-body infrared scanners (which measure skin temperature as a proxy for core body temperature), handheld infrared thermometers and ear gun thermometers. The latter two instruments were used in West African airports during the 2014 Ebola crisis, as a form of exit screening for those with ‘unexplained febrile illnesses’.

Unfortunately, none of these methods have proven entirely accurate. The risk is that they will flag up passengers who have a different type of infection, while missing those who are truly incubating the virus but haven’t started to show symptoms yet.

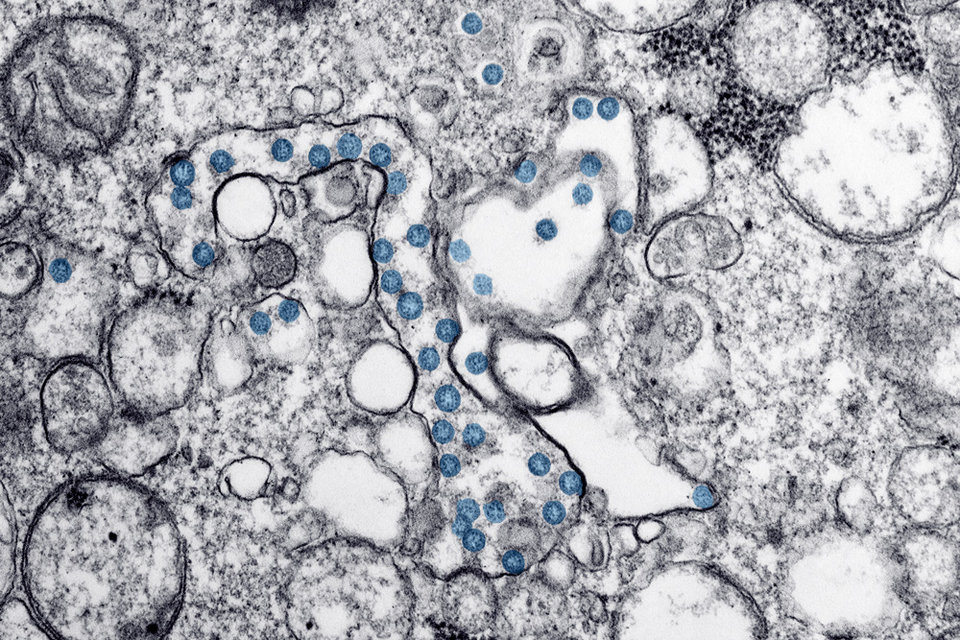

Transmission electron microscopic image of an isolate from the first US case of Covid-19. Image: US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

This was certainly the case during the SARS epidemic. While Canada saw 251 cases of SARS, the country’s intensive border screening failed to flag up a single one. Something similar may apply in the case of Covid-19. According to a CNN investigation, the US authorities had screened more than 30,000 passengers by mid-February without catching any cases. (At least four of these passengers later fell ill with coronavirus.)

At the end of January, a study from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (which has not been peer-reviewed) sought to quantify the effectiveness of thermal screening. It found that, out of every 100 infected travellers taking a 12-hour flight, 42 would pass through both entry and exit screening undetected.

This is mostly due to the incubation period of the virus, which can be as long as 14 days. An average incubation period of 5.2 days was assumed for this analysis. On top of that, some cases are mild and even at their peak may not show symptoms.

Billy Quilty, the lead study author, said: “Our work reinforces that thermal scanning cannot detect every traveller infected with this new coronavirus. Other policies that can decrease the risk of transmission from important infected individuals, such as providing information on rapidly seeking care if symptoms develop, are crucial.”

The ECDC has also completed modelling work to assess the effectiveness of entry screening. “Approximately 75% of cases from affected Chinese cities would arrive at their destination during the incubation period and thus remain undetected,” says Pommier.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the World Health Organization does not recommend thermal screening, stating in a release on 10 January: ‘It is generally considered that entry screening offers little benefit while requiring considerable resources.”

Thermal scanning cannot detect every traveller infected with this new coronavirus

What else can be done?

The question, then, is what else can be done to help control the spread of the coronavirus? Pommier believes that, at this stage, the best way to reduce the spread of infection is by rapidly identifying and testing any suspect cases, as well as identifying and monitoring anyone who has come into close contact with them.

“The population should be made aware of behaviours reducing the risk of transmission, for example self-isolation at home and seeking medical advice, should symptoms develop after exposure to one of the affected areas or a confirmed Covid-19 case,” she says.

Quarantining measures are scientifically very effective, since the person is isolated for the entirety of the potential incubation period. The US military has set up 11 quarantine camps next to major airports, which can accommodate up to 250 people each. And a hotel at Heathrow Airport had been block-booked to serve as a potential quarantine zone for people entering the UK with symptoms.

Basic health information is also very useful. In the US, passengers arriving from China receive a card telling them the symptoms to watch out for, and advising them to take their temperature twice a day. It seems this card may already be serving its intended purposes. In one case, a man (who had been asymptomatic at the airport and passed the screening checks) became ill the day after returning home. After consulting the card, he followed the advice to stay at home and contact his local health department.

In the EU, the authorities are being similarly vigilant. Pommier points out that healthcare settings have strong infection control measures in place, which should be sufficient to prevent any sustained local transmission in Europe. These measures have already proven effective in controlling SARS and MERS (which were both also forms of coronavirus).

However, despite airports’ and health authorities’ best efforts, some cases of coronavirus may probably slip through the net.

“At this stage, it is likely that there will be additional imported cases in Europe,” says Pommier. “When that happens, we need to ensure that the virus does not spread any further. ECDC is working with the member states to make sure that they are ready to manage imported cases, with laboratories capable of confirming probable cases and hospitals prepared to isolate and treat patients accordingly.”

The population should be made aware of behaviours reducing the risk of transmission