Technology

Sci-fly: the robots coming to an airport near you

UK-based company Engineered Arts recently showcased the world’s most advanced humanoid robot. Frankie Youd speaks to founder and director, Will Jackson, to find out about the potential benefits for the aviation industry.

From I, Robot to Terminator, humanoid robots have been gracing our movie screens for years. Soon they could be coming off the big screen and into our day-to-day lives in hospitals, shopping malls, and even in airports.

The UK’s leading designer and manufacturer of humanoid robots, Engineered Arts, has developed numerous robots for entertainment purposes. Last year they showcased something very special.

Developed by the company, Ameca is the reportedly world’s most advanced humanoid robot. Designed specifically as a platform for the development of robotics centred on human to robot interaction. By using a combination of AI, machine learning, and the company’s Tritum robot operating system, the Ameca’s behaviour can be changed as new situations are tested.

The AI and machine learning technologies found in Ameca’s mechanical mind are modular, meaning that it can be easily upgraded. Ameca’s head is also in the clouds (literally), with cloud-connected focus meaning that the company can access all the robotic data, and control and animate it from anywhere in the world.

Frankie Youd speaks to Engineered Arts founder and director, Will Jackson, to find out more about the benefits thatAmeca could bring to the aviation industry, as well as to discuss the issue of robot acceptance within society.

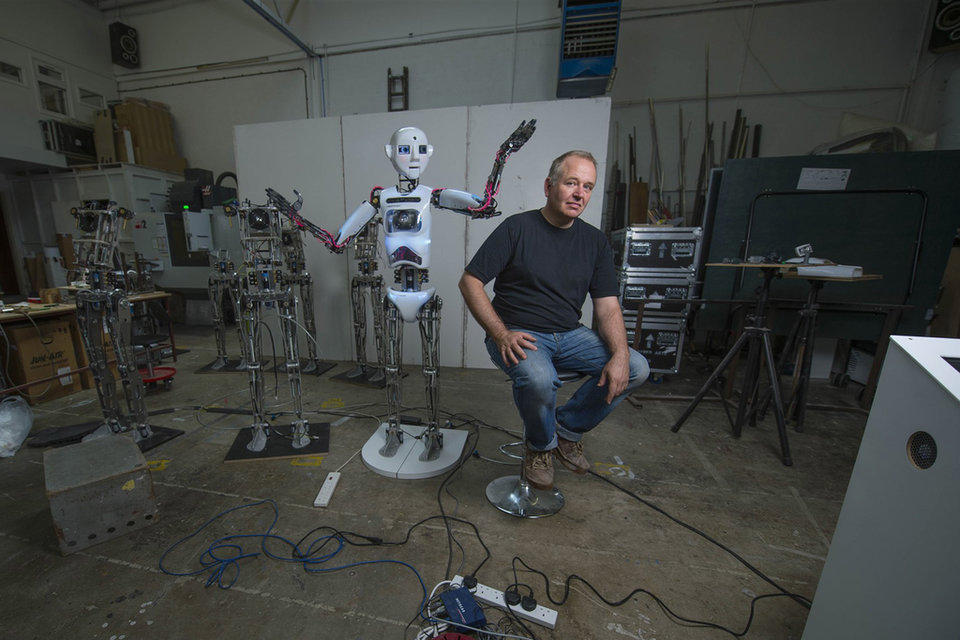

Engineered Arts founder and director, Will Jackson

Frankie Youd: Could you give some background on Engineered Arts?

Will Jackson: The company was founded in 2005. We’ve always made robots for public spaces. A big market section for us was science education: science museums, visitor attractions, that kind of thing. We’ve also supplied universities as a research platform.

Robots are always a kind of one-to-many proposition, a robot is an expensive thing. If you think about a car factory or something like that, you’ll have one production line robot that will make hundreds of thousands or millions of cars – so you can justify the cost of that expensive piece of equipment.

Think about a humanoid robot. What is the main reason for a humanoid robot? Why would you even make one? Why would you make it that shape? There’s a really nice illustration I always think about in the first Star Wars film: you have R2-D2 AND C-3PO, they are put into terms that everyone can understand. C-3P0 is the humanoid, multicoloured robot that most people don’t want.

There’s a nice scene where the scrap dealers have got that robot but nobody wants to buy it, because they ask: “What’s that for?” It’s the entertaining robot, it’s the one that does the translation it’s the one that talks to people. So, you have to think about where that robot would fit in the world that we live in now. It’s wherever there are lots of people.

What are the possibilities for robots in an airport environment?

In airports, you’ve got a lot of people who may need information or maybe they’re just bored waiting for their plane. You can imagine situations where a robot would work really well. If a passenger was stuck at the departure gate, their planes been delayed an hour, they’ve got three screaming children – there’s a robot over there that tells them stories.

Or say someone is completely lost, wandering around this airport terminal, they’ve got no idea where they should be going. It would be really helpful to have a robot assistant there that’s happy to talk to them and understand what they are saying.

Robots have many uses, from being an information point to entertainment, or just somewhere to pass time while you’re stuck in a queue. These are the kinds of applications we see now. You might sort of start thinking can it carry my bags? That’s harder to do with current technology, but it will get there.

With any new technology, you can imagine the way you want it to happen. But it’s quite often not what you expect.

As a company, we’re only just starting to explore this area. There’s a robot called Pepper that was brought out by SoftBank. I saw them in a cheese shop at the airport in Amsterdam. One of the problems with Pepper is it’s quite small, and airports can be quite noisy as well. You need to kind of be on eye level and you need to be much more sort of human one-to-one.

The other thing that we are finding is that an expressive capability that’s not voice is really important; knowing when somebody doesn’t want to be talked to. If the robot looks at somebody and the person just looks away, it should give up – they’re not interested in you. As people we know straight away, so bringing in those kinds of interactions, that capability, that’s what we’re interested in.

At the minute we would just be looking for partners who are wanting to try out the idea. That’s the kind of conversation we are exploring. Let’s set this up in an environment where we can monitor what happens, see how people respond to it, to see if we get a positive response, and see if there’s value here.

It’s about exploration. With any new technology you can imagine how people are going to use it, you can imagine the way you want it to happen. But it’s quite often not what you expect. We have to be flexible enough to realise that people may use it in a way you’ve never expected.

How does non-verbal communication come into the robot’s design?

Robots are aware of you right down to your facial expression; how much attention you’re paying to it; a reasonable estimation of where you’re going; and what kind of state you’re in, such as are they rushing to catch a plane or are they hanging around bored?

Machine learning now amazes me, we see new things all the time. I remember 10 years ago when we first started looking at hand gestures, we just wanted to pick up is somebody waving or not.

We just want to know if somebody’s trying to say hello, and then let’s wave back, and that was technically really hard to do 10 years ago. Then Microsoft brought out Kinect and we had structured type sensors and suddenly it became much easier to pick up what people were doing.

Still, it was a complicated piece of hardware. Now we’ve got to the point where you can use any ordinary cheap webcam and you could process that image and get a lot of really useful information. Even with just a low-cost webcam, we are able to pick up the pose of a person, their facial expression, right down to what each of their fingers are doing.

Suddenly all of that is so much easier, suddenly you can do all these things with applications, and we started asking things like can the robot do sign language? Yes, we’re moving towards that. We don’t have quite enough dexterity yet, but we can certainly recognise sign language.

Do you think that there is an increasing acceptance that robots will be part of day-to-day life?

I remember growing up in the 80s when television was the biggest evil of all time that destroyed the youth of today. Now, it's TikTok, Facebook, or something else destroying the youth. Today, it’s always whatever’s new that’s is evil.

This idea of humanoid robots is a very old one. It’s been a staple of science fiction all the way back to Fritz Lang’s Metropolis from 1927, this idea of a robot person is ongoing through history. It’s a bit of wish fulfilment when people see a robot: “Oh, it’s just like I, Robot from that film.”

A lot of people think it’s like Terminator – this is a big thing that we get. If technology wanted to do harm, it wouldn’t bother to disguise itself as a human to do it. There is no kind of AI that actually makes creative decisions, there is no consciousness. We tend to imagine that it’s thinking in the same way we think, but it doesn’t think it at all. What it does is it takes some data in, and it will make an action out.

Now with our robots, you can show them a hand and they’ll pay attention to a hand. That’s the programme that says hands are interesting, look at them. It doesn’t mean that the robot understands what it’s looking at. It’s just a very simple bit of code.

To us, we look at it and imagine there’s much more there than there really is, and then we think: “Now it’s going to get angry, it’s going to get upset and kill everyone.”

Robots don’t have emotions. They don’t have a thought process like that. They just do what they’re programmed to do.

We don’t have an actuator or motor that is anywhere near as good as a human muscle. There is no robotic solution where we could mimic a person because the human body is just incredibly capable. People should not be too afraid that they are going to be replaced because we are nowhere near that.

All images credit: Engineering Arts