Environment

Getting the UK’s sustainable aviation fuel industry off the ground

The need to comply with emission reduction targets is lighting a flame under developers of sustainable aviation fuel in the UK – but what does this fledgeling industry need to do to succeed? Luke Christou finds out.

The aviation industry accounts for just 2% of all human-induced CO2 emissions globally. Yet, with the UK setting itself an ambitious target of reducing greenhouse gas emissions to zero by 2050, greater efforts will be needed to eliminate aviation’s environmental impact.

Even though passenger numbers are anticipated to grow by 70% over the next 30 years, UK aviation has thrown its weight behind the target. Through industry coalition Sustainable Aviation (SA), many of the industry’s biggest players have committed to cutting emissions to zero for all departing flights by the 2050 deadline. However, achieving net-zero will require aviation to move away from petroleum-derived jet fuels.

Sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) – jet fuels produced using clean and sustainable (typically biological) sources and practices – are thought to be a key part of the solution. Over the next 20 years, SA members have committed £3.5bn in investment towards initiatives that will help the emerging industry to develop, and with the support of the government, the coalition believes that the UK could become a world leader in SAF production.

Finding a home for the UK’s sustainable aviation fuel industry

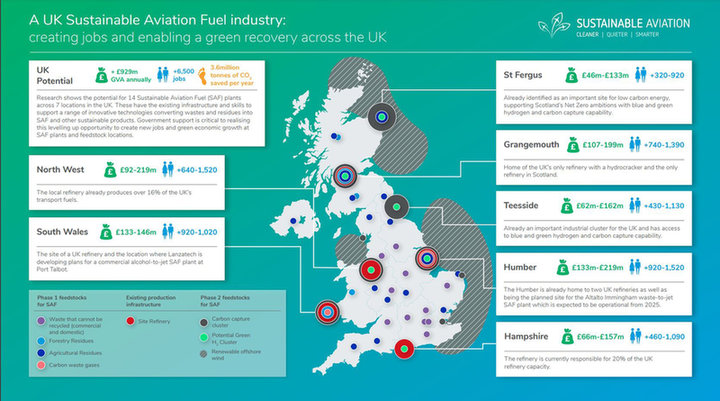

Key to elevating the UK’s status in the clean aviation technology industry will be the development of facilities capable of producing SAF at scale. New research carried out by energy consultancy E4tech on behalf of SA has identified major clusters that would offer prime conditions to support the growth of the UK’s SAF industry.

A total of seven areas were identified - Teesside, Humberside, the North West of England, South Wales, Southampton, St Fergus and Grangemouth - based on a range of factors, such as availability of feedstock and the presence of existing refineries, which could one day house 14 separate facilities.

SAF facilities can use a range of feedstocks including domestic and commercial wastes and gases that can’t be recycled

“SAF facilities can use a range of feedstocks, including domestic and commercial wastes and gases that can’t be recycled, plus agricultural residues and waste fats — these resources are located across the country, so we identified industrial hubs that can easily access them,” SA programme director Dr Andy Jefferson explains. “Similarly, we selected these locations due to their potential to utilise existing refineries and their associated infrastructure and skills.”

Likewise, the research also considered the UK’s plans to fund carbon capture, utilisation and storage (CCUS) clusters across the UK, with all seven of the regions identified by SAF already earmarked as future clean energy hubs.

“From around the mid-2030s, utilising CCUS technology and infrastructure can deliver further carbon savings from SAF delivery,” Jefferson insists. “By capturing and storing the carbon produced from the SAF process, it could become a negative emission fuel source and an even more desirable product for reaching net-zero emissions as a result.”

Placing SAF production facilities close by to CCUS hubs would also provide access to low-carbon hydrogen sources, such as blue hydrogen “for upgrading waste products into SAF” and green hydrogen to “power the conversion process”.

Many of the locations identified, including Immingham, Humber, are already home to oil refineries, which will offer immediate access to skilled workers. Credit: Budimir Jevtic / Shutterstock

A greener future

SA estimates that developing these facilities would help to save 3.6 million tonnes of CO2 annually, a reduction of almost 75% when compared with fossil fuels. However, the move won’t just benefit the environment.

“SAF investment can also help deliver a green economic recovery by creating future-proofed jobs in industrial regions where the facilities will be located, as well as in rural areas where the feedstock will be sourced,” Jefferson explains.

The research found that these facilities would offer 6,500 skilled jobs. Many of these would be created in areas where oil refineries currently exist, helping to replace jobs that are lost as we transition away from harmful fuels. In the North West, for instance, a production facility could offer up to 1,520 jobs, and Humber - currently home to two oil refineries - could benefit from a similar figure, which would boost the local economy by up to £219m.

Taking a leading role in the global SAF export market holds the potential for an increase of £1.97bn in gross added value

“Taking a leading role in the global SAF export market holds the potential for an increase of £1.97bn in gross added value and the creation of 13,700 jobs – a total of almost £3bn per annum from both production and exports, whilst also helping support the government’s ‘levelling-up’ agenda by delivering jobs and investment to areas in need,” Jefferson says.

However, in order to maximise the benefits of the emerging SAF economy, the UK must act fast to secure its place as a leader. The SA has called on the government to provide £500m in funding that would support the development of these facilities and help to get the industry off the ground.

“SAF will become an essential fuel for the global aviation industry in a net-zero world, and so the country that commercialises the technology first will capture the wealth of jobs and wider supply chain benefits on offer,” Jefferson insists. “The UK had the opportunity to act in a similar way with offshore wind a decade ago but didn’t move fast enough – we can’t let the opportunity pass this time around and find ourselves importing the equipment we need.”

An aerial view of the Velocys Altalto Immingham project site. Credit: Velocys Altalto Immingham project

An immediate impact

Of course, SAF won’t be the be-all and end-all. Electrification is also set to play a major role in reducing aviation’s environmental impact, with industry leaders across technology and transportation, such as Safran, Honeywell and Airbus, making significant progress towards electric flight.

“In our Decarbonisation Road-Map, we recognise that there is no silver bullet for dealing with aviation carbon emissions - electric, hybrid and hydrogen technologies all have great potential to deliver zero-emission short to medium-haul flights,” Jefferson says.

“Clearly, there remains a strong need to sustain the joint UK aerospace and government investment in the introduction of electric or hydrogen-powered aircraft, but it is all of these approaches together - including SAF - that are needed to ensure aviation can deliver on the net-zero emission goal.”

SAF can cut emissions within five years

However, SA believes that the development of SAF must take priority due to the immediate improvements that it can provide. “New aircraft technology is around ten years away before it enters service and has a dramatic step change in emissions,” Jefferson points out. “SAF can cut emissions within five years.”

Sustainable fuels technology company Altalto, a joint venture between British Airways, Shell and Velocys, has been granted permission to build a facility in Humber. The facility is set to convert hundreds of thousands of tonnes of non-recyclable household and commercial waste into SAF each year, with production set to begin as soon as 2025.

“SAF is a near-term opportunity, deploying proven technologies, meaning it can be used in existing engines and transportation pipelines requiring no modifications to aircraft or refuelling infrastructure,” Jefferson explains.

A close-up view of the planned Velocys Altalto site. Credit: Velocys Altalto Immingham project

Committing to net-zero aviation

Aviation has been among the industries worst hit by Covid-19. With fleets grounded for large parts of the year and flights down by close to 50% globally, the cost of the pandemic for aviation is expected to total up to $314bn.

As aviation begins its recovery, it would be easy for businesses to turn attention away from sustainability and focus on maximising profits and ensuring recovery instead. Yet, SA remains committed to delivering net-zero for aviation by 2050, “despite the massive impacts the industry has faced”.

However, it can’t do so alone — further support from the UK Government will be critical to achieving its goal.

The ambitious goal of reaching net-zero aviation remains achievable

So far, the signs are promising. In November, the government published 'The Ten Point Plan for a Green Industrial Revolution', which included a number of ‘Jet Zero’ initiatives designed to tackle aviation industry emissions. As part of the push, the UK is set to consult with experts on whether to introduce a mandate that would require aviation companies to use SAF, encouraging the industry to grow and, in turn, fuelling the UK’s green aviation industry.

“Although there is still a long way to go to make Britain the home for SAF, especially around price floors and loan guarantees, the ambitious goal of reaching net-zero aviation remains achievable,” Jefferson insists.

The development of SAF production facilities could provide a substantial boost to local economies. Credit: Sustainable Aviation